Unconcealed: The Man and his Art

by David Carson

Christchurch book store owner and writer, John Summers, described the young Peter Carson, in his autobiography Dreamscape as

…very shy, reserved, his very laugh at the ridiculousness of this or that choked off half-way through.

But he observed that

Behind the mild manner is a slightly disconcerting stare, indicative, maybe of that obsessive element within, so necessary to the outcast artist…

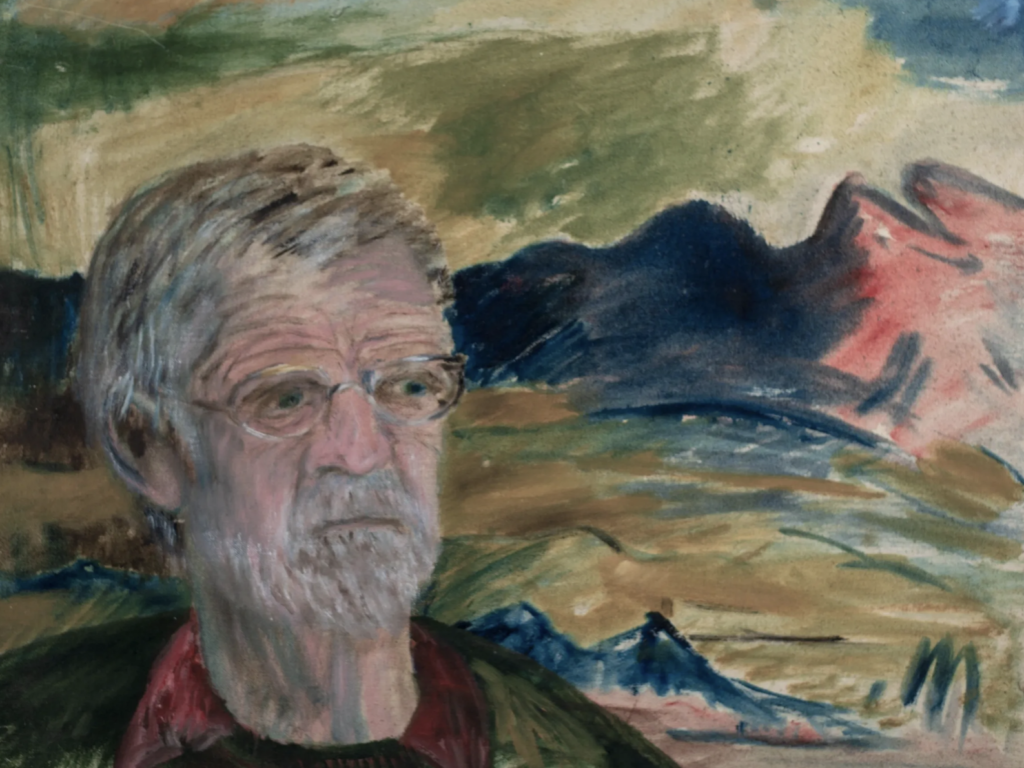

My father was an extremely guarded man, but Summer’s was an astute observer, glimpsing something that most others missed – an abnormal mentality. For those that knew Peter Carson through his job as a postman, or knew him casually, and even for those that knew him as a close friend, he was a well-spoken, gentle, humble, and a very friendly and generous person. He possessed a sweet and ready smile, he was always polite, and literally everyone who met him liked him immediately. He seemed on the outside to be content to the point of placidity. But behind this persona, there was a moody soul, prone to depression, and to fits of anger. In letters written to my mother in their courtship days he confessed to her that he was “troubled”. He told her that, if she wanted to know him, she should read the biographical account of the shy and tormented British war poet Edward Thomas (depicted below), written by his wife Helen in the volumes As it Was(1926) and World Without End (1931).

Thomas, who died after being “shot clean shot though the chest” in the Battle of Arras, is described by his wife as impatient, quick to violent anger, and subject to long periods of depression. He was also a great nature lover who frequently went for long solitary walks. My father wrote that the “David” of these books “has many traits (too many) of myself.”

I will lend the book to you, after reading it you will understand me better, I am sure, but I am still what I am.

He was around that time an aspiring poet and writer, but decided that he expressed himself better by image than by word (having read his early journals and his letters, I disagree, and say that he was a natural born writer who slowly but surely mastered the art of expressing himself visually). He warned her that “there is a streak of melancholy running through me” and “I like to be alone a lot.”

Art is Everything

When I was an adult, my father and I forged a strong bond based on our shared love of art, classical music, and literature, and we would visit art galleries together, and talk about these subjects. And, separated by the Tasman, we corresponded by post. But for most of my childhood, he kept himself aloof from family activities, and spent much of his time in his “painting shed”, and various other locations designated as the spaces in which he would paint, often while listening to classical music. He would rarely emerge in a good mood, and he was rarely in a good mood at any time. If not for my mother, and her organization of outings and holidays, I believe he would have done little else in life other than draw and paint, read and write, and go in search of artistic and literary inspiration. Aside from bush walks, or walks through natural landscapes, these were the only times I knew him to be happy. He worked for most of his adult life as a postman on a bike, since it both enabled him to be in the fresh air, and provided him with the time to paint (he rose at 5 am, started work at 6, and was home by midday, ready for an afternoon and evening of painting). He was at his retirement (following a slippage on black ice that resulted in a broken pelvis), the oldest postman in NZ postal history (74), testimony to his hardiness, but mainly to the strength of his disinterest in any occupation other than that of an artist.

My family belonged to a sectarian Christian group which met in private homes, and I remember that my father’s mood seemed to be at its lowest on these occasions. While he knew the bible from cover to cover, and could deliver a rousing sermon, and pray a deeply felt prayer, he found church-going uncomfortable. His “brethren” would never have suspected, but he was entirely out of place in a church setting: he disliked ceremonies and formalities of any kind, and he disliked socializing with more than one or two people at a time. But he had the quality of a chameleon – he could temporarily adapt himself to more or less any environment. The truth is that his church was nature, and he worshiped the force behind the natural world through his art.

Early Influences: Woollaston and McCahon

As a young man he moved in artistic circles. He was friendly with Sir Toss Woollaston (1910-1998) before the knighthood, and painted with him on the West Coast. He records in a letter to my mother a discussion between himself and Woollaston on the topic of favorite painters. Wooleston told him that his favorite painter was Cezanne, “if one can have a favorite.” My father responded “one can”, and at that time his favorite, he says in the same letter, was Woollaston himself. He was impressed by Woollaston, and also by Colin McCahon (1919-1987), citing his encounter with McCahon’s free copy of the Entombment of Christ by Titian as one of the most significant artistic experiences of his life (he produced his own Carsonesque version of Titian’s masterpiece).

But he outgrew his mentors. While he owned several Woollastons, and hung one on the wall of the family home, there is little to no trace of Wollaston’s influence in any but his earliest work (50s, 60s). His oil paintings in the 70s are somewhat abstract, somewhat geometric landscapes, McCahon-like to begin with it might be said, but increasingly reminiscent of work by the British landscape painter Samuel Palmer (1805-1881). My father could, and did, bang out Carsonesque Palmers with the greatest of ease.. He continued to admire Woollaston, McCahon, and Palmer throughout his career, but any stylistic similarities between himself and these artists are barely noticeable in work produced after the 70s. Later work by Peter Carson has a style that is unmistakably his own. But I well remember visiting his studio shortly after the death of Wooleston in 1998, and finding my father working in his second story studio on a portrait of Woollaston, in the style of Wollaston.

Tony Fomison

My father was friendly with his contemporary, Tony Fomison (1939-1990), even going so far as to invite the then homeless painter to stay with my mother and myself when I was an infant. My mother later told me that she was aware of Fomison’s reputation as a long-haired “druggie” and that she was very reluctant -afraid even- to have him stay. Unlike my father, she was from a conservative Christian background, but she was liberal enough to marry a man from the wrong side of the tracks, who was regarded by her mother as charming, good-looking, but an ill-educated “no-hoper”. My grandmother insisted that he improve his socio-economic status (he was working as a window cleaner at the time) before she would allow her daughter to marry him… Since she doesn’t remember, it is hard then to know if my mother was instrumental in preventing the visit of Fomison, but knowing her, and knowing Fomison, I’d say probably not. In any case, he never showed up, and this was a great relief to her.

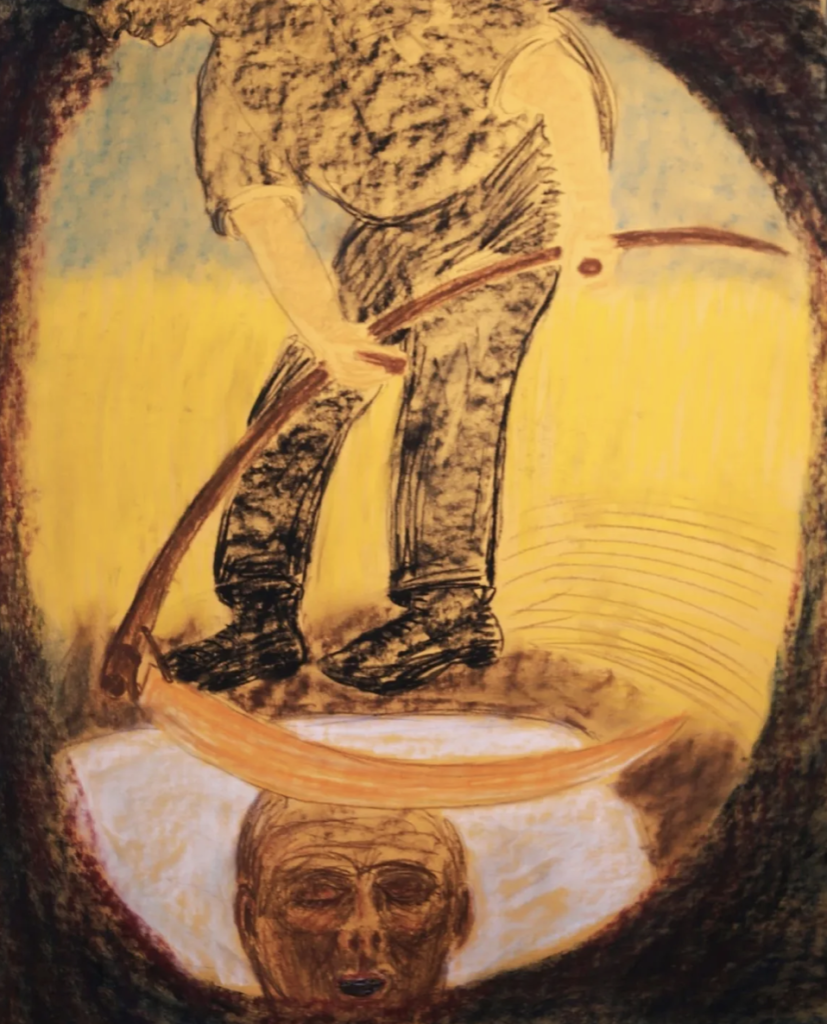

Like Fomison, my father was an outsider, and always had a great fondness and a sympathy for outsiders. He was reluctant to speak ill of anyone down on their luck and/or unaccepted or otherwise unappreciated or frowned upon by society at large. After discovering through DNA analysis that the name “Carson” was almost certainly a pseudonym for the name “MacGregor”, it occurred to me that maybe this attitude was in his blood. The name of this “wicked and unhappy” Scottish clan, I learned, was banned for nearly 2 centuries. MacGregors were from 1603 required by law to change their names, and large bounties were payable for the decapitated head of a MacGregor. The Campbells had a pit where MacGregors were chained prior to beheading. My father knew nothing whatever of this history but, following his death, I found amongst work retrieved from his studio a graphic and unusual pastel on the theme of beheading (also the victim appears to be in a pit).

Anyone found bearing the name MacGregor was, in 17th century Scotland, liable to be tortured and put to death. During that time many clansmen sought refuge in the mountains, and the MacGregors for that reason became known as the “Children of the Mist”.

Looking Beyond the Carson Sunsets

Peter Carson exhibited a number of times, and in a number of places over the years, most recently at the Chamber Gallery in Rangiora in 2019. But these exhibitions were always small, the work was usually chosen by the curators (or at least subject to the approval of the curators), and only dimly reflected the substance of my father’s extensive artistic output. He became known for romantic landscapes, and for so called “Carson Sunsets”, but anyone who has had the opportunity to examine the bulk of his work knows that -while these things exist- they are superficial, almost accidental, aspects of the art of Peter Carson. There is much more going on than this. If I was required to say in brief what is going on I would use words such as “moody” “dark” “intense” (chiaroscuro) “haunted” “phantasmagoric” and “apocalyptic”.

He was literally obsessed by the suffering and death of Jesus. While he painted on a variety of Christian themes, by far the most repetitive of these themes is that of the crucifixion and the events surrounding the crucifixion. It would be easily possible to dedicate an entire Peter Carson exhibition to this theme, and there would be literally hundreds of striking works to show. His art is spiritual, but in the Gnostic or Manichean, rather than the narrow Christian sense of that term.

One of the major influences on my father’s thinking was William Blake who wrote in the Marriage of Heaven and Hell that “without contraries there is no progression”. I remember that Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience was a much-thumbed book in my father’s library (I kept coming back to it myself). But unlike Blake my father found it difficult to portray innocence, to capture innocuous scenes that celebrate human life. He did not consciously desire or plan for this, but his forte was experience, and his characters -usually everyday rural people- appear alien or ghoulish, tortured even, and the landscapes in which he places them are foreboding.

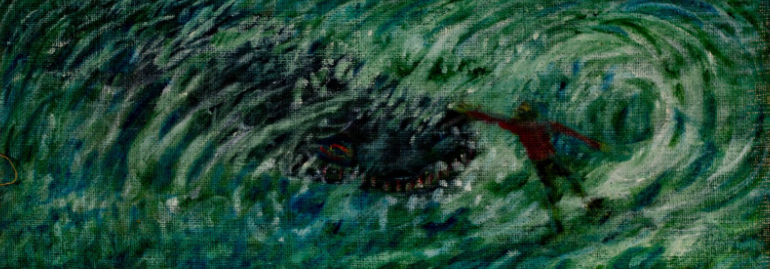

His empty landscapes (and seascapes) tend also to be suffused with tension and foreboding.

Sometimes the darkness is unambiguous.

And yet, strangely, literally none of his critics so far have thought to comment on any of this. Sculptor Lllew Summers (son of John), who used to exchange his sculptures for my father’s paintings, focuses on the romanticism and primitivism of a Carson:

When I think about Peter Carson’s work, the word that comes to mind is Romanticism…Peter’s links with history come from William Blake (1757-1827, Casper David Friedrich (174-1840), and Samuel Palmer (1805-1881)… Carson’s paintings are not academic, they are intuitive. His is a raw, simple, and honest vision. There is no shortage of skill in the world, but that is only one of the things that go into making art works. Vision cannot be taught and is absolutely necessary to create something of lasting beauty and value. Carson’s visionary work celebrates life and the wonders of the landscape.

Writer Anthony Holclroft, and one of my father’s best and oldest friends, focuses on the tendency of a Carson to spiritualize and therefore universalise the particular landscapes it depicts:

Peter Carson’s paintings are the expression of a searching, deeply felt response to the spirit of the land in which he lives. His work is strongly reginalist, securely embedded in the landscapes of the South Island, and to the casual observer it might appear somewhat narrow in focus. But that would be a superficial view. What defines these paintings is the way that the local landscape has been transformed by the imagination to create an intense, spiritual resonance… Carson has absorbed Samuel Palmer’s dictum,’Bits of Nature are generally much improved by being received into the soul.’, and applied it to his own native ground through his painterly explorations of light.

Summers, and Holcroft in particular, are right in what they say, and they present Peter Carson as he presented himself, but their account is both idealistic and incomplete. It glosses over the dark side of Peter Carson, and the tension there is in his work between dark and light. Nevermind the Carson sunsets, what about the Carson chiaroscuro? Nevermind Blake, David Freidich,and Palmer – when I contemplate Peter Carson’s use of light, I think back to Leonardo, Carrivagio, and particularly to Rembrandt. My mother has always said that she doesn’t like my father’s paintings because a) he imposes his internal vision on the world rather than reflects what the eye can see and b) that vision is a dark vision. She claims that it was her role in the relationship to keep him from succumbing to despair, and that at times she found him so unpleasant to be around that she regretted the marriage. It seems to me that in some ways she is his most astute critic.

The Hessian Scrolls

A decade or so ago, when I was visiting my parents from Australia, my father showed me some of his latest work, and described to me a painting technique that he had developed. He would paint on the coarse fabric hessian, but would not glue the hessian to a board or even frame it. Rather he would pin the hessian to a flat surface such as a desk, and after thickly applying paint to the fabric, would allow it to be absorbed overnight. The next day he would apply a further layer of paint, and allow that to be absorbed…and so on until he was satisfied that the painting was maximally impactful. The effect, he told me, was a greater clarity and richness than he had been able to produce by painting on canvas, hardboard, or hessian glued to hardboard.

There was, he suggested, an organic quality to these paintings that was missing in his previous oil works. He painted over 200 of these “hessian scrolls” (as I call them) before his death, and was of the opinion that they constituted his very best work as a painter. He produced over the course of his career over 4000 paintings, pastels and drawings, but in my judgment, there is no potential collection of works by Peter Carson that better displays in a unified way his artistic vision, a vision that has been in large part obscured from view. With or without the assistance of a gallery, I plan to stage a Peter Carson exhibition that presents a breadth of work unified by medium and by message, and which accurately represents the vision and the capabilities of the artist.There is no better candidate exhibition, IMO, than an exhibition of the Hessian Scrolls. These are presently unframed, and they should not IMO be framed or mounted, but pinned to the wall, their scroll-like nature and their ragged edges clear for viewers to see…

The Unadorned Facts

Peter Carson was born in Christchurch in 1938 and grew up on a farm at Harewood. He was educated at Harewood School and Papanui High School. In 1953 he was apprenticed as a book-binder at the Canterbury Public Library where he was to work for 10 years. At about the same time, he began drawing and painting with the encouragement of John Summers, at whose bookshop he met Toss Woollaston with whom he would later paint on the West Coast.

In 1959, he participated in group shows at Gallery 91. Charles Brasch purchased drawings from his first one man show at John Summers Bookshop in 1963. Having left his library job in an attempt to paint full time, in the mid-sixties he moved to Rangiora, where he worked as a postman from 1968 until 2012, painting in the afternoons after his round. He has had numerous exhibitions: at Several Arts; the CSA; Salamander Gallery; Under the Red Verandah; and the Chambers Gallery, Rangiora. The Christchurch Art Gallery purchased his painting The Rain in the Hills in 2002. His paintings also appear in the Hocken Collections, the Macmillan Brown Library, and the Rangiora Library.

He died in an Oxford Rest Home in 2022 from complications following Covid 19.